When I was in the 7th grade, I found a treasure. It was bright blue, like a robin’s egg, but unlike any egg, this particular parcel was one of nature’s enduring mysteries: the chrysalis of a monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus).

I brought the pupa case, branch attached, in to my science class, and we put it in a jar near a window. Over the course of some days, the chrysalis darkened, showing clearly identifiable butterfly parts within. Eventually, a dark incised line appeared near the top of the pupa case, and when that line finally encircled the top, a very weak and wrinkled adult butterfly struggled out. Once dry, it climbed out of our jar and launched itself straight out the open window.

I brought the pupa case, branch attached, in to my science class, and we put it in a jar near a window. Over the course of some days, the chrysalis darkened, showing clearly identifiable butterfly parts within. Eventually, a dark incised line appeared near the top of the pupa case, and when that line finally encircled the top, a very weak and wrinkled adult butterfly struggled out. Once dry, it climbed out of our jar and launched itself straight out the open window.

This was in Utah in the early 1990s, and around the same time, one of the small trees in our front yard was completely inundated with monarch butterflies. Migrating southward, it would seem, just a quick stop along its jaunt from Canada to Mexico. I’d never seen anything like it before, and if you’ve seen any of the news lately, you may not have many chances to see it again.

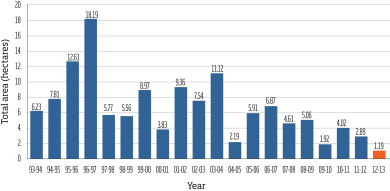

In last winter’s survey (2012-13) of the butterfly’s overwintering grounds in several Mexican forests, only 1.19 hectares, or just about 2 acres, were found to be hosting significant colonies of the migrating species. Compare with with the high of 18.19 hectares (almost 45 acres) in 1995-96. Numbers have generally been on the decline every year since then, with fluctuations up and down, but never to the point where they are now.

North American Leaders Urged to Restore Monarch Butterfly’s Habitat, nudges today’s New York Times (Feb. 14, 2014).

Monarch butterflies deserve executive attention, proclaims an editorial yesterday’s Boston Globe (Feb. 13, 2014)

Carlos Slim! Mexican billionaire tycoon throws in a not insubstantial amount of his own funds to rescue this iconic butterfly species (Feb. 10, 2014).

Why?

To put it dramatically, the butterflies are running out of food. Literally starving. This is a result of a two-fold problem: harsh climate fluctuations and a diminishing food source.

Putting aside the issue of the increasingly hot North American summers that kill the fragile monarch larvae before they hatch, a more controllable issue for gardeners and butterfly-lovers is the plants on which these butterflies’ larvae feed. Monarch larvae rely on members of the milkweed family (Asclepias), known to kids and non-gardening types for their glossy puffs of wind-blown seed. Farmers, however, don’t find these plants charming at all, especially growers of corn and soy. Corn and soy acreage has exploded in the last 20 years, in part thanks to genetic modifications that make the cash crops resistant to herbicides like Roundup (glyphosate). Thus freed to spray weeds with abandon without danger to their crops, farmers have unleashed chemical doom on beneficial native weeds and other plants alike, resulting in fewer and far more fragmented feeding zones for the ever diminishing hordes of monarch butterflies.

It’s true, milkweed is, well, a weed. It reseeds freely and blows willy-nilly in the wind when the pods ripen in late summer. But folks, can you forgive the plant if it’s gorgeous? It’s easy enough to deadhead when it’s done blooming, right along with other perennials you wish to avoid spreading about. It surely deserves a place in anyone’s garden. Have a look.

Selections and cultivars of swamp milkweed and butterfly milkweed are probably the easiest to find in any nursery that offers any native plants, but mail-order outfits like Prairie Moon and Plant Delights carry one or more species of milkweed. They’re long-blooming, tough plants; my own swamp milkweed was absolutely covered in bees and butterflies virtually all summer long.

You might laugh, or outright scoff at the idea of planting a weed. But remember, a weed is defined as a plant out of place. If you want it, it’s not a weed anymore–especially when it’s serving not only an aesthetic purpose but an ecological one, as well.

Find a sunny, sort of soggy (or well-mulched) spot for a milkweed in your yard or garden. The monarchs will thank you.

Read more about milkweed and monarchs here:

U.S. Forest Service: Milkweeds and Nectar Sources

U.S. Forest Service: Milkweed Species Beneficial to the Monarch Butterfly

MonarchWatch.org: Monarch Butterfly Survey Points to Lowest Numbers in 20 Years